Many new axolotl owners get worried when their pet suddenly becomes quiet and stops exploring the tank in cold weather. This is when they start asking, “Do axolotls hibernate or migrate?” It can look scary if you’re used to seeing your axolotl swim around and then one day it just sits in one spot most of the time.

The good news is that this behavior is often normal. Axolotls do not hibernate like bears, and they do not migrate like birds or some fish. Instead, when the water gets cooler, their body naturally slows down, so they move less, eat less, and spend more time resting, but they are still awake and aware. This gentle slowdown is part of their normal cold‑water behavior.

In this article, you’ll learn why axolotls slow down in cold water, what brumation is, why they don’t need to hibernate or migrate, and how you can keep their tank cool, clean, and stable so your axolotl stays healthy all year round.

Do Axolotls Hibernate? The Truth Behind the Myth

Many people assume axolotls must hibernate in winter because they slow down when the water gets cold. In reality, axolotls do not go into true hibernation like bears or some other mammals. Instead, they enter a lighter, low‑energy state where they move less and eat less, but they stay awake and responsive.

This slowdown is their normal way of coping with cooler water, not a deep sleep that lasts for months. As long as the temperature stays within a safe range and your axolotl still reacts to food and movement, this behavior is usually nothing to worry about because it is simply a normal cold‑water slowdown.

What Is Hibernation vs. What Axolotls Actually Do

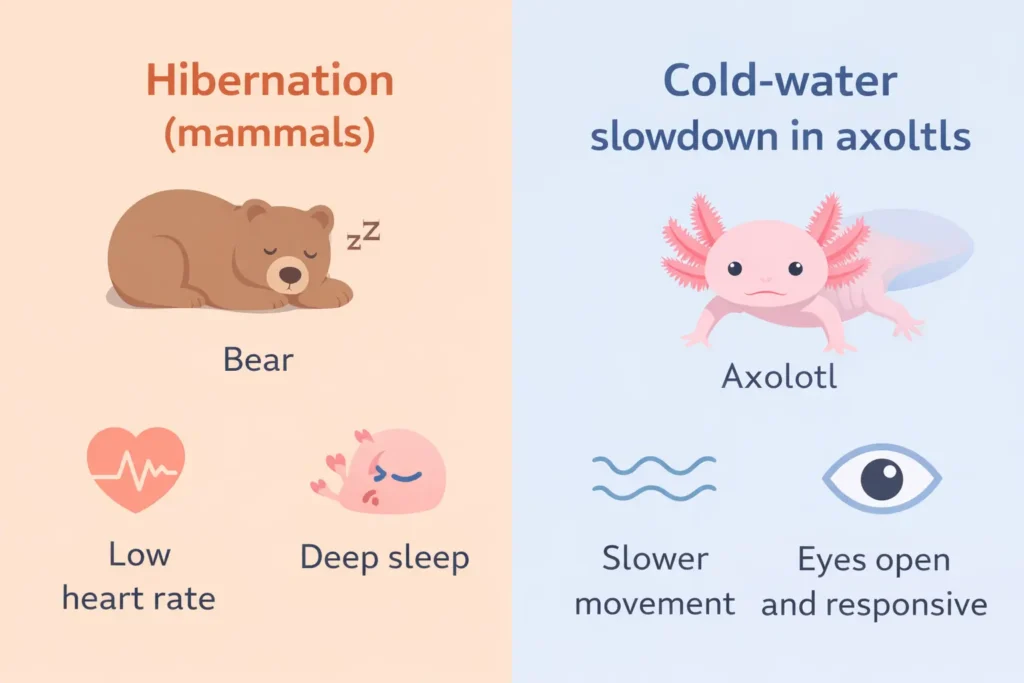

Hibernation is a deep, long‑term “shut‑down” that some animals use to survive harsh winters. During hibernation, body temperature drops a lot, the heart beats very slowly, breathing becomes shallow, and the animal does not wake up easily. Many mammals, like bears or hedgehogs, use hibernation to save energy when food and warmth are hard to find.

Axolotls do something different. When the water gets cooler, their metabolism slows down, so they use less energy. They may sit in one place for a long time, swim less, and eat less than usual, but they are still alert.

If you offer food or tap near the tank, a healthy axolotl will usually react, even if it is moving slowly. This lighter slowdown is closer to a mild brumation‑style state, not full, deep hibernation.

Why Axolotls Don’t Need to Hibernate

In the wild, axolotls live in cool, spring‑fed lakes and canals where the water temperature is fairly stable throughout the year. Because their environment doesn’t freeze solid or swing between extreme hot and cold, they never needed to evolve true hibernation to survive. The water simply gets cooler, and their body naturally slows down to match it.

In captivity, a well‑kept axolotl tank should also stay within a safe, cool range, so there is no reason for deep hibernation. If the water is kept cool, clean, and stable, your axolotl can stay healthy and comfortable all year round with only a gentle slowdown in colder periods.

This is why they don’t need to hibernate like other animals—and why you should focus on stable water conditions instead of trying to “make” them hibernate.

What Is Brumation? The Key Difference You Need to Know

When water gets colder, axolotls don’t go into a deep, long sleep like some animals do. Instead, they enter a lighter “slow‑down” phase called brumation. In this state, their body uses less energy, they move less, and they often eat less, but they are still awake and can respond if you offer food or tap near the tank.

Brumation is the way many cold‑blooded animals, like reptiles and some amphibians, cope with cooler seasons. Their environment cools down, so their body naturally slows its metabolism to match. For axolotls, this usually happens when the water is cool but still within a safe range, not freezing.

Understanding brumation is important because it stops you from panicking when your axolotl suddenly becomes quiet in winter. It also helps you recognize the difference between a normal seasonal slow‑down and real stress or sickness.

Brumation vs. Hibernation: What’s the Difference?

Hibernation and brumation sound similar, but they are not the same.

Hibernation

Hibernation happens mostly in warm‑blooded animals like bears and hedgehogs. In hibernation, the animal goes into a very deep sleep for a long time, its heart rate and breathing drop a lot, and it doesn’t wake up easily until the season changes.

Brumation

Brumation, on the other hand, happens in cold‑blooded animals like reptiles and some amphibians. During brumation, the animal slows down but does not completely “switch off.” It can wake up, move a bit, drink water, or even change spots, then go back to resting again. This stop‑and‑start pattern is normal for brumation and is much lighter than true hibernation.

So, the big difference is depth and awareness: hibernating animals are in deep sleep and stay that way, while brumating animals are just in low‑energy mode and can wake up from time to time.

Do Axolotls Brumate? Yes—Here’s How

Yes, axolotls can experience a mild form of brumation when the water is cool. You might notice your axolotl:

- Sitting in one place for long periods

- Swimming less than usual

- Eating less often, or refusing food some days

- Looking calm and relaxed rather than active and exploring

Even in this state, a healthy axolotl will usually react if you gently move something near it, turn on the light, or offer food. It is not “gone” like a hibernating animal—it is just conserving energy.

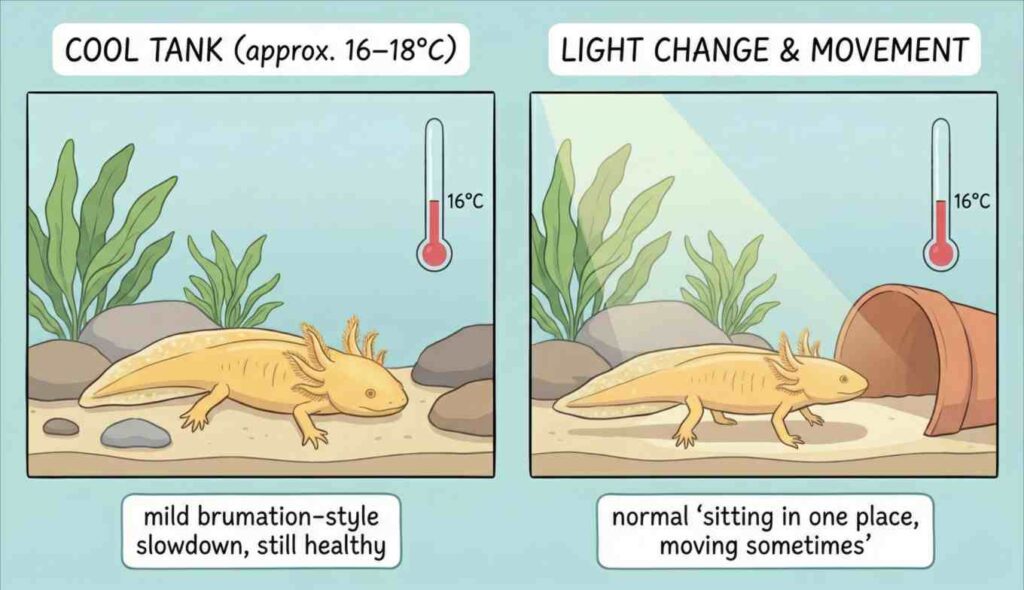

For example, in winter you might see your axolotl spending most of the day on the same rock or hide, only moving when you offer food or when the lights change. That is normal brumation‑style behavior as long as the water temperature is safe and there are no stress or illness signs like curled gills, floating, or red, irritated skin.

How Long Does Axolotl Brumation Last?

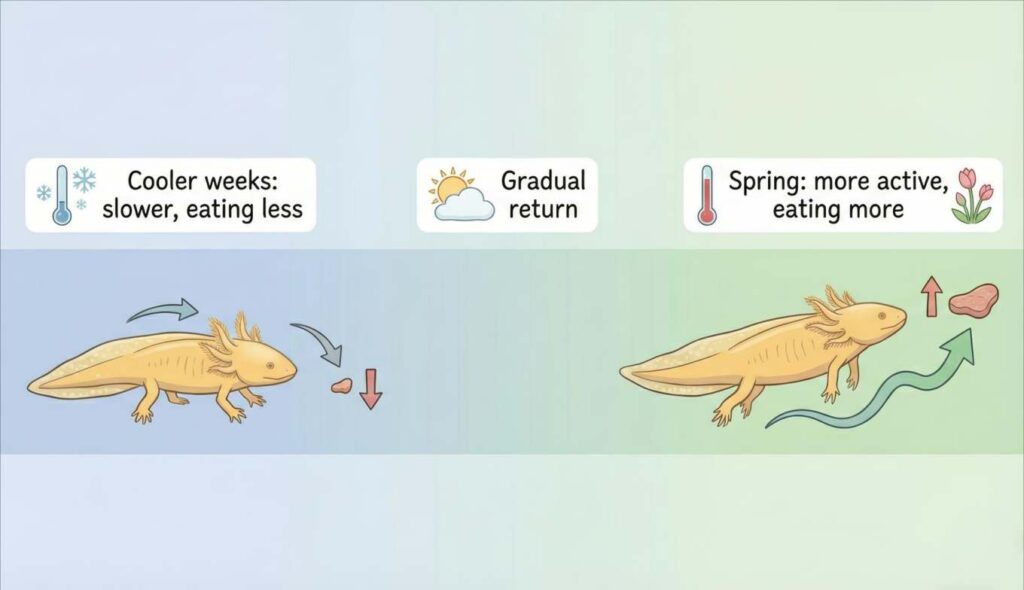

There is no fixed “brumation schedule” for axolotls, and it is usually lighter and shorter than in many reptiles. How long they stay in this slow‑down mode depends on:

- How long the water stays cool

- How stable the temperature is

- The individual axolotl’s health and age

In many home tanks, axolotls may act slower for a few weeks to a couple of months during the coldest part of the year. As the room and water warm up again, they usually become more active, start eating more, and go back to their normal behavior on their own.

If your axolotl is very inactive for a long time, stops eating completely, or shows other worrying signs (like weight loss, fungus, or constant floating), then it may not be simple brumation and you should treat it as a possible health issue, not normal seasonal behavior.

Do Axolotls Migrate? Why They Stay in One Place

Axolotls do not migrate like birds, whales, or some fish that travel long distances when seasons change. Instead, they usually spend their whole lives in the same lake, canal, or wetland area. In nature, their world is quite small compared to animals that cross oceans or continents.

Because they already live in cool, fairly stable water, they don’t need to move to find better temperatures. As long as the water stays cool, oxygen‑rich, and safe from pollution and predators, an axolotl is perfectly happy to stay in one place.

For pet axolotls, this is similar: if the tank feels safe and the water is clean and cool, they have no reason to “travel” or constantly move around.

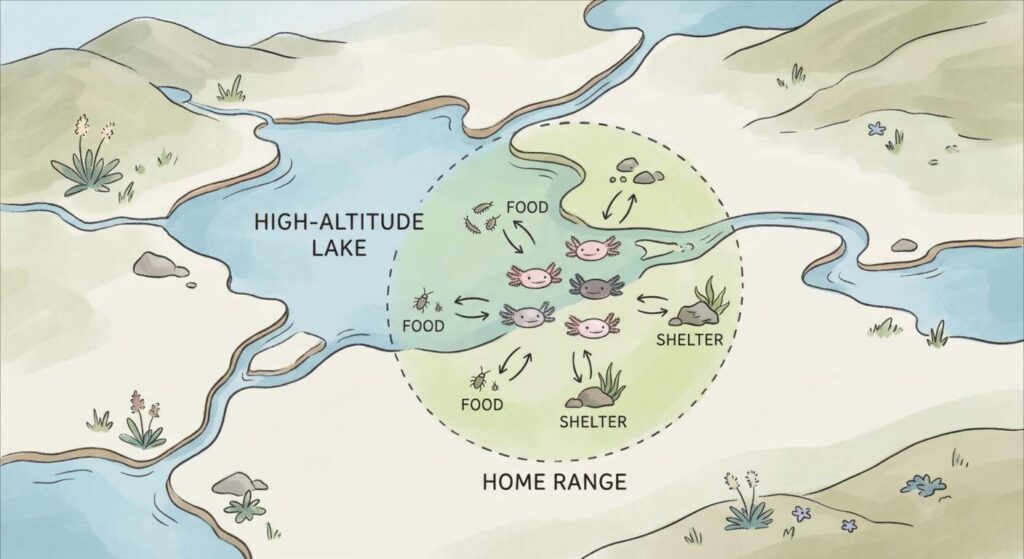

Axolotl Migration in the Wild

In the wild, axolotls are found in lakes and connected canals rather than in fast‑moving rivers or open seas. They may explore different parts of the same water system, but they do not travel long distances with the seasons. Their movements are usually small‑scale—looking for food, hiding spots, or mates—not full migrations.

Researchers studying axolotls in natural and restored wetlands have seen that they tend to stay within a limited home range. They may move tens of meters in a day to forage or find shelter, but they still remain within the same general habitat instead of leaving it to search for a new lake somewhere else.

Temperature Range for Axolotls: Ideal vs. Stress vs. Danger

Axolotls are very sensitive to water temperature, so even a small change can affect their behavior and health. Keeping the tank in a safe range is one of the most important parts of axolotl care. If the water is too warm or too cold, your axolotl can become stressed, stop eating, or even get sick.

In general, axolotls do best in cool water, not warm. Most keepers aim for a range around 60–65°F (16–18°C), which is close to the conditions in their natural habitat. Warmer water speeds up their metabolism and increases stress, while very cold water can make them weak and overly sluggish.

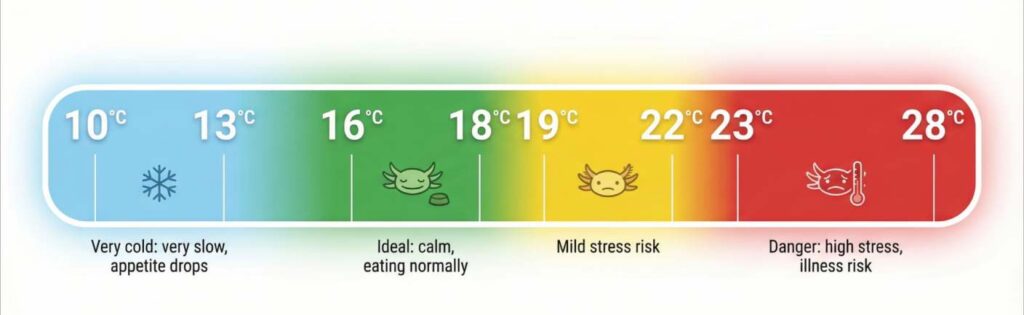

Here is a simple way to understand the main temperature zones for axolotls:

- Ideal zone (about 60–65°F / 16–18°C):

Your axolotl is calm, alert, and eats normally. This is the “sweet spot” where they are most comfortable and long‑term health is best. - Mild stress zone (about 66–72°F / 19–22°C):

Your axolotl may still be okay, but this range is warmer than they like. You might notice less activity, mild stress signs, or a reduced appetite if the water stays here for too long, which means you should start cooling the tank. - Danger zone (above roughly 73°F / 23°C):

This is risky for axolotls because warm water holds less oxygen and pushes their body to work harder. Long exposure can lead to stress, illness, infections, and in serious cases, death, so if the temperature reaches this range, you need to cool the water as soon as possible. - Too cold (below roughly 55°F / 13°C):

Axolotls can survive in quite cool water, but if it gets very cold, they become extremely slow and may stop eating for long periods. Short‑term cool spells are usually not a problem, but very low temperatures for a long time can weaken their immune system and overall health.

For most homes, the safest approach is to use a thermometer, check the water daily in summer and winter, and aim to keep the tank as close to the ideal range as possible. If you see the temperature creeping up into the warm or danger zone, that’s your signal to use cooling methods or improve your tank setup to protect your axolotl.

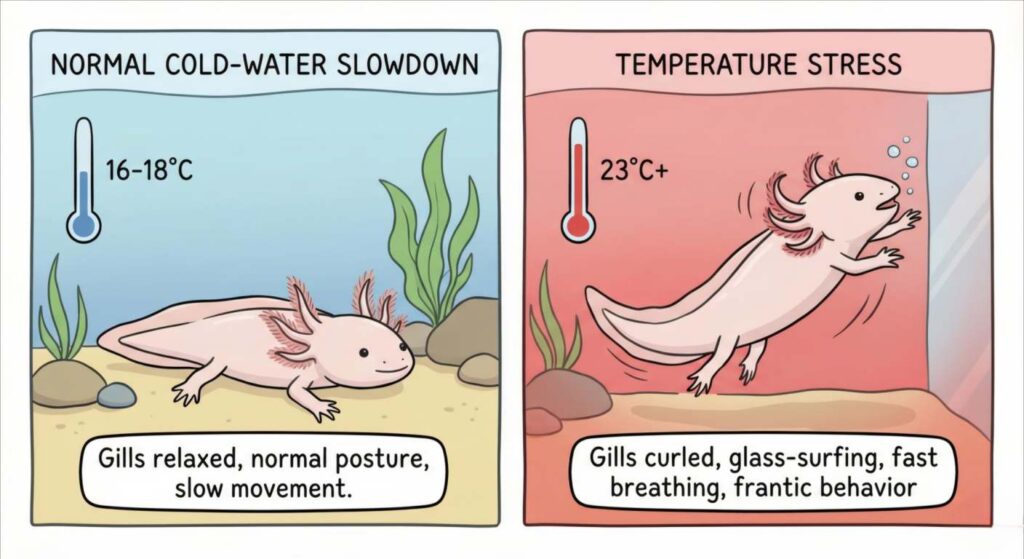

How to Tell If Your Axolotl Is Stressed From Temperature

When the water temperature is wrong, your axolotl usually “tells” you with its behavior. If the water is too warm, you might see it breathing fast, with the gills moving quickly and curling forward.

It can start swimming up and down the glass, floating around restlessly, or refusing food for several days. The skin may also look red, irritated, or much paler than normal, which are all signs that your axolotl is uncomfortable and needs cooler water.

Normal cold‑weather slowdown looks much softer and calmer than this. In cool but safe water, your axolotl will often move less, sit in one favorite spot for a long time, and eat less often, but it still reacts when you come near or offer food. Its breathing stays steady, not rushed, and it doesn’t look like it’s panicking.

If your axolotl is slow but calm in safe temperatures, it is usually just enjoying a natural cold‑water slowdown; if it looks panicked, sick, or the water is too warm, treat it as a temperature or health problem, not simple brumation.

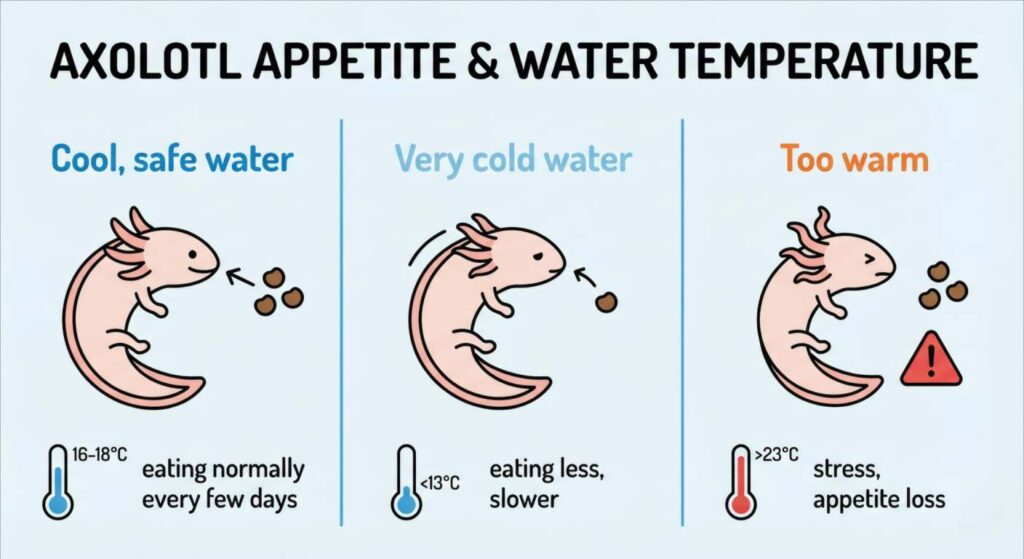

Does Temperature Affect Axolotl Eating?

Yes, temperature definitely changes how much your axolotl wants to eat. In cool, normal water they usually eat well and stay active, but when the water gets colder their body slows down and they naturally eat less.

Warmer water can also make them stop eating, but there it’s because of stress, which is more risky.

When the water is cool but in a safe range, many axolotls still eat, just not as often. They might skip a meal or take food more slowly, and that’s usually normal. In very cold water, they may refuse food for a while, but if they still look healthy and are reacting normally, it’s often just their metabolism slowing down.

You should start worrying when your axolotl stops eating for several days in a row and also looks unwell—breathing fast, curling its gills, swimming strangely, or losing weight.

A healthy adult can handle missing some meals, especially in cold water, but no food for a long time plus other stress signs means you need to check temperature, water quality, and possibly get help.

Conclusion

Axolotls neither hibernate nor migrate like many other animals; they simply slow down in cool water, eating and moving less while staying awake and aware. As long as you keep their tank cool, clean, and stable—ideally around 16–18°C (60–65°F)—this gentle slowdown is normal and healthy, not a reason to panic.

Focusing on safe temperature, calm behavior, and steady eating patterns will do far more for your axolotl’s health than trying to “make” it hibernate or worrying about migration.

FAQs

Do axolotls migrate or hibernate?

Some people think axolotls might migrate or hibernate like other cold‑blooded animals, but they don’t. They live their whole lives in the water and keep their gilled form, so they never turn into land‑living salamanders like other species. Instead of true hibernation or long travel, they simply slow down and become less active when it gets cold. This quiet, low‑energy period is a normal response to cooler water, not full hibernation or migration.

What do axolotls do in the winter?

In winter, axolotls usually get slower and calmer, but they don’t hide underground like mole salamanders or Tiger salamanders in North America. Those salamanders use burrows and crevices to escape freezing temperatures, while axolotls live in water that stays cool but doesn’t freeze solid. Because of this, they mostly stay where they are, move less, and eat less instead of making big seasonal movements.

What is the lifespan of an axolotl?

Axolotl lifespan depends a lot on where they live. In the wild, they often survive only about 5–6 years because of predators, pollution, and habitat loss. In captivity, with good care, they can reach up to around 10–15 years. A stable, quiet tank setup with clean water and proper food helps them stay more active, look healthier, and live closer to that upper range. They also mature quite early, usually reaching reproductive age in their first year of life.

Why do axolotls turn into salamanders?

Axolotls are naturally neotenic, which means they normally keep their juvenile, gilled form for life and stay in the water. In rare cases, though, they can undergo metamorphosis and turn into terrestrial salamanders.

This usually happens only when strong external factors are involved, such as hormonal manipulation or very harsh environmental conditions. Transformed axolotls look like other land amphibians and can sometimes still reproduce, but most axolotls never change and remain water‑based their entire lives.